THE debate around SA’s statues has shown up one lack of capacity among South Africans: knowledge of their own history. Some Afrikaners got deeply upset about the removal of Cecil John Rhodes’ statue at the University of Cape Town, forgetting what he did to instigate the genocidal Anglo-Boer War.

The postcolonial storm troopers of the Economic Freedom Fighters attacked the statue of a man who had once been a living symbol all across Europe of insurrection against the British Empire, Paul Kruger. In Durban the statue of Fernando Pessoa was desecrated, with only a handful of South Africans knowing that he was one of the 20th century’s greatest poets, who had spent his formative years in SA.

But even worse than no history is a distorted history. A little while ago commentators on former president Thabo Mbeki’s legacy were upbraided for lionising him just because his successor is a disaster. Now, in the midst of a new wave of xenophobia, Mbeki’s selective praise singers are at it again, cherry-picking his utterances in 2008 to show up the Zuma administration’s lack of leadership in 2015.

Notably absent from all the quotes is one that said more about that outbreak and the current one than any other utterance by an ANC leader: The 2008 xenophobia was no xenophobia because whites were not being attacked. The implication, of course, being that whites, being settlers of a special type, are foreigners, with the further implication that if violence against black foreigners is warranted, then it is also against whites.

Mbeki’s other catastrophic utterance, not of the same order as King Goodwill Zwelithini’s incitements against foreigners, but with the same effect, was that South Africans should open their arms to Zimbabweans fleeing because of the difficult conflict resolution it was undergoing.

I still remember how alarmed I was, watching the buildup of xenophobic tension about the effect that statement would have after another breakdown in the so-called "peace talks". Within days, dozens of people had been murdered.

Through his deft diplomacy Mbeki duped world leaders and key South African media people into casting the violent and systematic suppression of the opposition in a purported democracy as just another African bush conflict. This not only destroyed what little remained of any belief among Zimbabweans that democracy could work, sending many of them across the border, it also reinforced the legend among other Africans that SA was a refuge from Africa’s many other bush conflicts.

Mbeki’s definition of xenophobia that it should involve whites was either another misjudgment from SA’s arch-denialist, going with his denial of HIV, Robert Mugabe’s evil, and the electricity grid, or an expression of general African National Congress sentiment.

Whichever it was, there is a direct link with the strange flailing about of Zuma Cabinet members such as Police Minister Nathi Nhleko in describing the event in Durban as Afrophobia, avoiding the term xenophobia.

Experts on xenophobia wrote after 2008 that what was really at stake was the continuing project of a rising South African nationalism. Because it is so indeterminate and in flux, the quest for what a South African is, is often tested against what they are not, hence is expressed in a loathing and fear of other identities that might be stronger than your own fragile identity.

And just how fragile that identity is, has been demonstrated by the statue storming all over the country, with the common denominator being not the Rhodes-centred anti-colonialism that gained the support of large numbers of whites, but anything that is not "African". The reflected truth was of another sort of delivery service failure, that not many statues of African heroes had been erected after 1994, and that where memorials do exist, such as for the Cradock Four or Robben Island, these are often in a state of severe decay.

A key concept in discussions of xenophobia is the "other", which is usually taken to mean people who are not like you, followed by moralistic injunctions along the lines of "love thy neighbour".

But in deconstructing that word "Afrophobia" one might look at the first usages of the term "other", as by a key western philosopher GWF Hegel. For him, the "other" was an internal construct — what one has to come to terms with is not always the threatening neighbour, but the dynamics of your own psyche. Indeed, "love thy neighbour" is followed by "as you would love thyself".

That it is not really about an "other" outside oneself, is further demonstrated by the strange exclusion of whites — in defiance of Mbeki’s secret wish list — from the black South Africans’ xenophobic project when it comes to the practical side of things. It is almost as if the xenophobics are saying: leave our whites for us, go back to your own (who are often officials from aid programmes). Of course, this stands in contrast with the current bout of white-bashing riding on the slogan of "check your privilege" circulating on social media.

At the heart of both these phenomena is the unspoken demand that whites have to do something about their continued postcolonial advantage. Just when whites thought they had been relieved of the "white man’s burden" of colonial times, they are now being implored to drive transformation fuelled by the "white man’s guilt".

That is where the foreigners are so threatening. Africa’s conflicts act as a kind of Darwinian natural selection, sending the cream from populations suffering them out into other parts of the world. It is often an ordeal to reach rumoured havens such as SA, only the tough and determined succeed. It is now accepted even in government circles that they are outdoing local competitors in many respects.

But the reason is not a lack of talent here; it lies in the attitude towards the whites as the perceived masters of the economy and the demand that they deliver restitution on terms determined by the black majority in various expressions of historically derived entitlement.

Paying apartheid wages, for instance, is not good anymore in an ethos of transformation. South Africans believe they are entitled to what they call a "living wage", even when this puts them at a distinct disadvantage in a globalised economy.

This campaign of very long standing is fraught with tensions over the limitations of such demands, and is really hanging by the thread of a solidarity which is still rooted in struggle times — and which is being further unravelled by the collapse of the Congress of South African Trade Unions.

The daily demonstration by law-abiding foreigners right outside your door that there is another solution, based on temporary slave labour conditions and the solidarity of capitalistic networking, can be a real threat to this dated anti-apartheid consensus. Hence the "Afrophobia", which is really the fear of the failure of the unrealistic projections in yourself.

• Pienaar is a subeditor

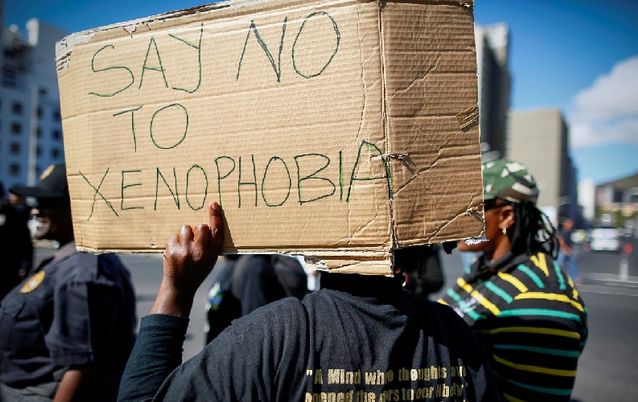

Xenophobia poster. Picture: EPA/NIC BOTHMA

THE debate around SA’s statues has shown up one lack of capacity among South Africans: knowledge of their own history. Some Afrikaners got deeply upset about the removal of Cecil John Rhodes’ statue at the University of Cape Town, forgetting what he did to instigate the genocidal Anglo-Boer War.

The postcolonial storm troopers of the Economic Freedom Fighters attacked the statue of a man who had once been a living symbol all across Europe of insurrection against the British Empire, Paul Kruger. In Durban the statue of Fernando Pessoa was desecrated, with only a handful of South Africans knowing that he was one of the 20th century’s greatest poets, who had spent his formative years in SA.

But even worse than no history is a distorted history. A little while ago commentators on former president Thabo Mbeki’s legacy were upbraided for lionising him just because his successor is a disaster. Now, in the midst of a new wave of xenophobia, Mbeki’s selective praise singers are at it again, cherry-picking his utterances in 2008 to show up the Zuma administration’s lack of leadership in 2015.

Notably absent from all the quotes is one that said more about that outbreak and the current one than any other utterance by an ANC leader: The 2008 xenophobia was no xenophobia because whites were not being attacked. The implication, of course, being that whites, being settlers of a special type, are foreigners, with the further implication that if violence against black foreigners is warranted, then it is also against whites.

Mbeki’s other catastrophic utterance, not of the same order as King Goodwill Zwelithini’s incitements against foreigners, but with the same effect, was that South Africans should open their arms to Zimbabweans fleeing because of the difficult conflict resolution it was undergoing.

I still remember how alarmed I was, watching the buildup of xenophobic tension about the effect that statement would have after another breakdown in the so-called "peace talks". Within days, dozens of people had been murdered.

Through his deft diplomacy Mbeki duped world leaders and key South African media people into casting the violent and systematic suppression of the opposition in a purported democracy as just another African bush conflict. This not only destroyed what little remained of any belief among Zimbabweans that democracy could work, sending many of them across the border, it also reinforced the legend among other Africans that SA was a refuge from Africa’s many other bush conflicts.

Mbeki’s definition of xenophobia that it should involve whites was either another misjudgment from SA’s arch-denialist, going with his denial of HIV, Robert Mugabe’s evil, and the electricity grid, or an expression of general African National Congress sentiment.

Whichever it was, there is a direct link with the strange flailing about of Zuma Cabinet members such as Police Minister Nathi Nhleko in describing the event in Durban as Afrophobia, avoiding the term xenophobia.

Experts on xenophobia wrote after 2008 that what was really at stake was the continuing project of a rising South African nationalism. Because it is so indeterminate and in flux, the quest for what a South African is, is often tested against what they are not, hence is expressed in a loathing and fear of other identities that might be stronger than your own fragile identity.

And just how fragile that identity is, has been demonstrated by the statue storming all over the country, with the common denominator being not the Rhodes-centred anti-colonialism that gained the support of large numbers of whites, but anything that is not "African". The reflected truth was of another sort of delivery service failure, that not many statues of African heroes had been erected after 1994, and that where memorials do exist, such as for the Cradock Four or Robben Island, these are often in a state of severe decay.

A key concept in discussions of xenophobia is the "other", which is usually taken to mean people who are not like you, followed by moralistic injunctions along the lines of "love thy neighbour".

But in deconstructing that word "Afrophobia" one might look at the first usages of the term "other", as by a key western philosopher GWF Hegel. For him, the "other" was an internal construct — what one has to come to terms with is not always the threatening neighbour, but the dynamics of your own psyche. Indeed, "love thy neighbour" is followed by "as you would love thyself".

That it is not really about an "other" outside oneself, is further demonstrated by the strange exclusion of whites — in defiance of Mbeki’s secret wish list — from the black South Africans’ xenophobic project when it comes to the practical side of things. It is almost as if the xenophobics are saying: leave our whites for us, go back to your own (who are often officials from aid programmes). Of course, this stands in contrast with the current bout of white-bashing riding on the slogan of "check your privilege" circulating on social media.

At the heart of both these phenomena is the unspoken demand that whites have to do something about their continued postcolonial advantage. Just when whites thought they had been relieved of the "white man’s burden" of colonial times, they are now being implored to drive transformation fuelled by the "white man’s guilt".

That is where the foreigners are so threatening. Africa’s conflicts act as a kind of Darwinian natural selection, sending the cream from populations suffering them out into other parts of the world. It is often an ordeal to reach rumoured havens such as SA, only the tough and determined succeed. It is now accepted even in government circles that they are outdoing local competitors in many respects.

But the reason is not a lack of talent here; it lies in the attitude towards the whites as the perceived masters of the economy and the demand that they deliver restitution on terms determined by the black majority in various expressions of historically derived entitlement.

Paying apartheid wages, for instance, is not good anymore in an ethos of transformation. South Africans believe they are entitled to what they call a "living wage", even when this puts them at a distinct disadvantage in a globalised economy.

This campaign of very long standing is fraught with tensions over the limitations of such demands, and is really hanging by the thread of a solidarity which is still rooted in struggle times — and which is being further unravelled by the collapse of the Congress of South African Trade Unions.

The daily demonstration by law-abiding foreigners right outside your door that there is another solution, based on temporary slave labour conditions and the solidarity of capitalistic networking, can be a real threat to this dated anti-apartheid consensus. Hence the "Afrophobia", which is really the fear of the failure of the unrealistic projections in yourself.

• Pienaar is a subeditor

Post a comment